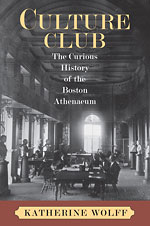

Culture Club

Scouting for books and fibbing to booksellers, three bibliomaniacs—William Smith Shaw, Arthur Maynard Walter, and Joseph Stevens Buckminster—shaped the early library of the Boston Athenaeum

In the early nineteenth century, though books were still scarce in America, bibliomania was no rare disease. The same transatlantic pipeline that brought news of William Roscoe’s excellent character fed a growing appetite for books, pamphlets, and magazines. Like Roscoe [founder of the Liverpool Athenaeum], for whom the “arrangement and cataloging of books … afforded the greatest pleasure,” William Smith Shaw fell victim to a “bibliomaniacal affection.” Both men became familiar with the work of the Reverend Thomas Frognall Dibdin, for example, whose playful 1809 volume The Bibliomania: Or, Book-Madness; Containing Some Account of the History, Symptoms, and Cure of This Fatal Disease, ushered in what one commentator has called the heroic age of book collecting. Most of Shaw’s intimate friends shared his habit. Epitomized by the harvesting activity of the Athenaeum’s emblematic putti, collecting was popular among amateur men of letters such as Shaw and Walter.i And it was to London that these collectors looked. In 1810, as the gentlewoman Anne Cabot Lowell writes to a friend, “even those who cherish other prejudices have none against the literature of G. Britain—they look there for all their models. They despise an American book.”ii

Accordingly, Arthur Maynard Walter’s book lust, never hidden in his correspondence with Shaw, took on a more confident tone when he crossed the Atlantic in 1802:

Literature is my object. I shall buy a good library in London. I shall expend $1,500 in law books and a private, choice collection. I mean to buy the cornerstones of my learning. These must support the building; and others, gradually attained, must contribute to its strength and beauty. The gigantic names of Cudworth, Locke, Milton, Selden, and others will be obtained, and, if money be sufficient, my library will not be small. There is a pathway open in this country to a goodly land. I mean to offer my passport at the turnpike-gate.iii

Employing metaphors from both architecture and exploration, Walter’s announcement is typical of the jumbled excitement that characterized book purchasing at this time. The last two sentences imply special access, an entrée into heretofore forbidden territory. Walter’s eagerness to be let into London’s storied bookstores is matched only by his bravado in declaring that his large budget should meet his needs. He is an informed collector, but he clearly wants to return with as many books as possible. For men set on accumulating private libraries, size did matter.

Many scholars have commented on the hidden psychology of collecting, claming, for example, that “the ubiquity of collecting is one of the most telling facts of nineteenth-century upper-class history.” While undoubtedly a source of pleasure and prestige, collecting is also said to be the individual’s way of compensating for real or imagined failures, an effort to reduce anxiety, an experiment in self-healing.iv Certainly a review of William Smith Shaw’s life shows that such impulses were at play there: the loss of a beloved friend pinched Shaw’s heart and concentrated his focus on collecting, for himself as well as for the young reading room. The despair associated with the low status of American letters, a despair voiced by Shaw and others, motivated the men in his circle to help him in his cause. Although its origins were ultimately personal, the Boston Athenaeum gradually adopted a public face. In the collecting efforts made on its behalf, one detects a shared institutional drive to amass the tokens of learning—and to assert Americans’ worthiness as cultural consumers.v

The mechanics of William Shaw’s long-distance collecting reveals anxieties inherent in the task. Instead of dealing directly with London booksellers, Shaw worked through agents who bought the books and had them sent back on merchant ships. (One such vessel, the Amelia, was, conveniently, owned by a friend of the Athenaeum who charged no fee for the literary cargo.)vi Shaw’s correspondence with his longtime friend Joseph Buckminster, the Athenaeum’s first official “book scout,” helps us understand the obstacles encountered. Buckminster had traveled to Europe seeking a cure for his worsening epilepsy. A popular Boston minister who enjoyed a reputation for energizing biblical scholarship until his death in 1812, at age twenty-eight, Buckminster was the more remote member of the friendly triad that had included Walter and Shaw.vii According to book historian James Raven, whose study of the Charleston Library Society chronicles another early American institution’s participation in the transatlantic book trade, “Social imperatives loomed large in maintaining the attraction of imported books. American book imports were lifelines of identity, and they were direct material links to a present and past European culture.” The phrase “lifelines to identity” tantalizes with connotations of a high-stakes rescue mission. Shaw’s desperation becomes evident in the text of his correspondence. If, as David Hall asserts, “the history of learned culture is a history of the strategies that scholars, reformers, and intellectual entrepreneurs devised to overcome the scarcity of resources and the absence of centers of authority,” then it pays to trace the strategies represented in Shaw’s letters abroad.”viii